BART - A Bayesian machine learning workflow for complex spatial data

In our recent publication from 2020, we analyzed COVID-19 incidence and socioeconomic, infrastructural, and built environment characteristics using a multimethod approach. Germany has 401 counties, which vary greatly in size. Counties in Southern Germany are generally smaller and have higher population densities. The figure below shows the natural log-transformed, age-adjusted COVID-19 incidence rates as of April 1, 2020, highlighting spatial differences between the northeast and the south-southwest.

After conducting a thorough spatial exploratory analysis, we applied a Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART; (Chipman, George, and McCulloch 2010)) model to identify socioeconomic and built environment covariates associated with COVID-19 incidence. BART is an ensemble-of-trees method, similar to random forests (Breiman 2001) and stochastic gradient boosting (Friedman 2002). Tree-based regression models are flexible enough to capture interactions and non-linearities. Summation-of-trees models (such as BART or random forests) can capture even more complex relationships than single-tree models. However, BART differs from these common algorithms because it uses an underlying Bayesian probability model rather than a purely algorithmic approach (Kapelner and Bleich 2016). One key advantage of the Bayesian framework is that it computes posterior distributions to approximate the model parameters. These priors help prevent any single regression tree from dominating the ensemble, thus lowering the risk of overfitting (Kapelner and Bleich 2016; Scarpone et al. 2020).

For our analysis, we used the R package bartMachine (Kapelner and Bleich 2016). One caveat is that bartMachine does not support tibble objects as input features, but aside from that it is intuitive and simple to use.

In this post, I will illustrate how we used the same data from our COVID-19 paper to analyze age-adjusted incidence rates in German counties using BART. Even though the BART model has strong predictive capabilities, we will not use it to forecast new COVID-19 cases. Instead, we will use it as an exploratory tool to understand which factors influence the spread of COVID-19 and how they interact with incidence rates.

I want to emphasize that we are only examining data from a single date, April 1, 2020, covering the first wave of the pandemic in Germany. A friend of mine is currently investigating which factors contributed to the second and third waves. Although some variables remain important across different time points, others gain or lose relevance, and in some cases the direction of their effects appears reversed.

In sum, BART is used here as an exploratory tool, and we will generate Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to visualize and interpret the marginal effects of key predictors.

If you are interested in more detail about pre-modeling exploratory data analysis or data engineering, please see the paper or contact me.

Data download and pre-processing

First, we need to load the packages and set the memory size and number of cores for bartMachine.

# Set to use 45 GB memory - adjust this to your resources

options(java.parameters = "-Xmx45g")

# Load packages

library(bartMachine)

library(dplyr)

# Set to run on 20 threads - adjust this to your resources

set_bart_machine_num_cores(20)

## bartMachine now using 20 cores.

Tip: Double-check that the correct amount of RAM is being allocated after loading bartMachine. If the message shows a different number, try manually typing out the java.parameters string instead of copy-pasting.

Next, we download the data and normalize the church density variable (Rch_den).e.

# Function for linear stretching. New range: 0-1

range0_1 <- function(x){(x-min(x))/(max(x)-min(x))}

# Download data

data <- read.csv("https://github.com/CHEST-Lab/BART_Covid-19/raw/master/Data/GermanyTraining.csv",

stringsAsFactors = F) %>%

mutate(Rch_den = range0_1(Rch_den),

NUTS2_Fact = as.factor(NUTS2_Fact),

BL_ID = as.factor(BL),

S_109 = as.factor(S_109))

# Select variables: Lat/ Long, BL, NUTS2, socioeconomic, build environment and age adjusted case rate

data <- data[c(374, 3, 4, 5, 38, 28, 65:372)]

| AdjRate | X | Y | NUTS2_Fact | BL_ID | EWZ | S_001 | S_002 | S_003 | S_004 | S_005 | S_006 | S_007 | S_008 | S_009 | S_010 | S_011 | S_012 | S_013 | S_014 | S_015 | S_016 | S_017 | S_018 | S_019 | S_020 | S_021 | S_022 | S_023 | S_024 | S_025 | S_026 | S_027 | S_028 | S_029 | S_030 | S_031 | S_032 | S_033 | S_034 | S_035 | S_036 | S_037 | S_038 | S_039 | S_040 | S_041 | S_042 | S_043 | S_044 | S_045 | S_046 | S_047 | S_048 | S_049 | S_050 | S_051 | S_052 | S_053 | S_054 | S_055 | S_056 | S_057 | S_058 | S_059 | S_060 | S_061 | S_062 | S_063 | S_064 | S_065 | S_066 | S_067 | S_068 | S_069 | S_070 | S_071 | S_072 | S_073 | S_074 | S_075 | S_076 | S_077 | S_078 | S_079 | S_080 | S_081 | S_082 | S_083 | S_084 | S_085 | S_086 | S_087 | S_088 | S_089 | S_090 | S_091 | S_092 | S_093 | S_094 | S_095 | S_096 | S_097 | S_098 | S_099 | S_100 | S_101 | S_102 | S_103 | S_104 | S_105 | S_106 | S_107 | S_108 | S_109 | S_110 | S_111 | S_112 | S_113 | S_114 | S_115 | S_116 | S_117 | S_118 | S_119 | S_120 | S_121 | S_122 | S_123 | S_124 | S_125 | S_126 | S_127 | S_128 | S_129 | S_130 | S_131 | S_132 | S_133 | S_134 | S_135 | S_136 | S_137 | S_138 | S_139 | S_140 | S_141 | S_142 | S_143 | S_144 | S_145 | S_146 | S_147 | S_148 | S_149 | S_150 | S_151 | S_152 | S_153 | S_154 | S_155 | S_156 | S_157 | S_158 | S_159 | S_160 | S_161 | S_162 | S_163 | S_164 | S_165 | S_166 | S_167 | S_168 | S_169 | S_170 | S_171 | S_172 | S_173 | S_174 | S_175 | S_176 | M_km2 | T_km2 | P_km2 | S_km2 | T_km2_1 | All_R_2 | M_pop | T_pop | P_pop | S_pop | T_pop_1 | All_R_p | tot_R | lib_km2 | uni_km2 | sch_km2 | cll_km2 | kid_km2 | ply_km2 | the_km2 | ngh_km2 | cin_km2 | pub_km2 | bar_km2 | std_km2 | sc_km2 | hsp_km2 | doc_km2 | mll_km2 | dc_km2 | con_km2 | sup_km2 | pst_km2 | th_km2 | cc_km2 | nh_km2 | ac_km2 | phr_km2 | rst_km2 | ff_km2 | caf_km2 | fc_km2 | bir_km2 | bak_km2 | chm_km2 | dot_km2 | har_km2 | prk_km2 | Rch_km2 | Rmu_km2 | Rth_km2 | All_P_2 | lib_pop | uni_pop | sch_pop | coll_pp | kid_pop | play_pp | thea_pp | nigh_pp | cin_pop | pub_pop | bar_pop | stad_pp | sc_pop | hosp_pp | doc_pop | mall_pp | dc_pop | con_pop | sup_pop | post_pp | th_pop | cc_pop | nh_pop | ac_pop | phar_pp | rest_pp | ff_pop | cafe_pp | fc_pop | bier_pp | bake_pp | chem_pp | doit_pp | hair_pp | park_pp | Rch_pop | Rmu_pop | Roth_pp | All_P_p | tot_P | lib_den | uni_den | sch_den | coll_dn | kid_den | play_dn | thea_dn | nigh_dn | cin_den | pub_den | bar_den | stad_dn | sc_den | hosp_dn | doc_den | mall_dn | dc_den | con_den | sup_den | post_dn | th_den | cc_den | nh_den | ac_den | phar_dn | rest_dn | ff_den | cafe_dn | fc_den | bier_dn | bake_dn | chem_dn | doit_dn | hair_dn | park_dn | Rch_den | Rmu_den | Roth_dn | All_P_d | Pop_Den |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27.37 | 9.44 | 54.78 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 89504 | 8.9 | 76.0 | 19.3 | 7.9 | 12.5 | 43.8 | 14.5 | 60.3 | 8.1 | 31.8 | 94.8 | 24.1 | -10.9 | 72.1 | 27.7 | 44.1 | 51.8 | 18.8 | 48.6 | 22.8 | 39.9 | 17.2 | 32.9 | 85.0 | 74.5 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 5.5 | 9.8 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 23.8 | 19.6 | 9.6 | 20.2 | 10.6 | 8.2 | 2.4 | 42.2 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 19.0 | 30.2 | 14.3 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 0.75 | 78.80 | 2.3 | 70.3 | 48.2 | 34.0 | 92.1 | 109.0 | 44.7 | 13.2 | 91.2 | 9.8 | 29.5 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 15.7 | 14.0 | 2.91 | 1527 | 2333 | 1278.6 | 2986 | 16.0 | 17.6 | 24258 | 11.3 | 3375 | 2992 | 3373 | 2965.5 | 3.8 | 52.6 | 24.4 | 6.4 | 40.9 | 1.0 | 14.9 | 4568.9 | 444.4 | 50.4 | 15.6 | 27.1 | -2.4 | 9.47 | 369.1 | 29.6 | 30.1 | 100.3 | 55.7 | 123.9 | 35.2 | 15.8 | 92.5 | 45.2 | 69.1 | 7.0 | 371.4 | 1282.4 | 1.3 | 767.3 | 0.0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 156 | 2309 | 13725 | 16.2 | 23.5 | 19.6 | 26.5 | 7.2 | 19.1 | 7.41 | 25.6 | 134.5 | 6.24 | 1.80 | 5.1 | 5 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 500 | 92 | 543 | 90 | 602 | 89 | 180 | 100 | 478 | 52.4 | 34.2 | 27.7 | 14.0 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 19.8 | 3.5 | 40.1 | 1.6 | 131.7 | 30.9 | 6.23 | 42.5 | 62.0 | 18.1 | 25.3 | 5.8 | 67.8 | 8.5 | 1.9 | 35.2 | 92.5 | 100.0 | 42826.6 | 4.1 | 51.8 | 24.8 | 97.0 | 34.8 | 48.8 | 16.4 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.95 | 2.45 | 0.00 | 33.81 | 24.40 | 24.01 | 52.45 | 134.66 | 120.52 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 1.67 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 1.71 | 1.24 | 0.85 | 0 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 1.26 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 12.46 | 4.47 | 0.00 | 4.47 | 3.35 | 16.76 | 91.62 | 5.59 | 6.70 | 2.23 | 50.28 | 4.47 | 0 | 4.47 | 0.00 | 50.28 | 0.00 | 2.23 | 16.76 | 22.35 | 11.17 | 0.00 | 6.70 | 0.00 | 3.35 | 20.11 | 93.85 | 68.15 | 46.93 | 0 | 0.00 | 55.86 | 12.29 | 2.23 | 69.27 | 1.12 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 3.35 | 684.89 | 613 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.33 | 4566 |

| 49.54 | 10.13 | 54.32 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 247548 | 9.1 | 72.0 | 22.6 | 6.6 | 8.9 | 33.1 | 14.9 | 63.2 | 8.8 | 37.8 | 310.5 | 3.2 | 136.2 | 67.3 | 32.4 | 38.9 | 51.5 | 19.2 | 48.9 | 21.3 | 39.3 | 17.5 | 32.6 | 79.2 | 67.7 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 26.5 | 19.1 | 8.8 | 18.5 | 9.7 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 41.5 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 17.8 | 26.7 | 1.6 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 0.64 | 80.05 | 5.0 | 73.5 | 31.1 | 41.7 | 90.4 | 140.6 | 31.4 | 13.4 | 127.9 | 9.4 | 30.3 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 13.9 | 20.5 | 4.56 | 1564 | 27 | 1293.2 | 3304 | 12.1 | 14.5 | 35 | 18.2 | 4015 | 3296 | 3693 | 3844.7 | 6.0 | 54.4 | 28.7 | 5.8 | 27.7 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 886.5 | 383.0 | 51.7 | 17.1 | 31.5 | 7.3 | 9.84 | 295.2 | 30.1 | 26.0 | 74.6 | 67.8 | 88.6 | 34.9 | 30.2 | 91.0 | 67.0 | 39.6 | 7.3 | 399.2 | 2269.4 | 74.5 | 755.3 | 53.4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 209 | 3112 | 22801 | 16.9 | 17.7 | 17.4 | 26.2 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 5.25 | 30.2 | 146.1 | 7.31 | 1.91 | 6.6 | 2 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 460 | 92 | 415 | 94 | 590 | 89 | 193 | 100 | 436 | 49.1 | 30.3 | 27.1 | 13.1 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 17.9 | 2.9 | 21.0 | 2.0 | 120.2 | 30.6 | 6.96 | 45.7 | 66.4 | 18.3 | 30.0 | 5.9 | 108.1 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 34.9 | 91.0 | 0.0 | 45821.3 | 4.6 | 51.5 | 26.0 | 97.5 | 38.3 | 48.1 | 13.6 | 0.20 | 0.69 | 0.14 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 2.37 | 9.06 | 31.13 | 6.29 | 30.83 | 30.10 | 107.42 | 265.92 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 1.34 | 1.35 | 0.81 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 10.75 | 4.85 | 0.00 | 2.83 | 1.62 | 14.95 | 23.83 | 2.02 | 4.85 | 2.83 | 23.03 | 14.95 | 0 | 9.70 | 0.00 | 30.30 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 7.68 | 25.45 | 11.31 | 0.81 | 1.62 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 27.47 | 60.59 | 61.40 | 36.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 42.01 | 7.68 | 3.64 | 49.69 | 0.40 | 7.27 | 2.83 | 1.62 | 487.18 | 1206 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.20 | 0 | 0.10 | 0 | 0 | 0.30 | 6862 |

| 43.20 | 10.73 | 53.87 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 217198 | 8.6 | 69.7 | 26.5 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 35.7 | 17.2 | 58.0 | 8.5 | 36.3 | 176.7 | 18.6 | 52.5 | 75.6 | 24.3 | 40.5 | 56.1 | 18.5 | 48.4 | 21.0 | 46.9 | 17.6 | 31.9 | 81.1 | 85.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 10.0 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 25.0 | 21.5 | 10.5 | 23.2 | 12.7 | 9.6 | 3.1 | 44.7 | 2.2 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 19.5 | 36.1 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 12.7 | 0.72 | 79.62 | 1.0 | 70.7 | 54.5 | 43.0 | 104.4 | 49.2 | 22.7 | 16.3 | 60.1 | 10.0 | 25.6 | 4.6 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 14.2 | 2.81 | 163 | 2593 | 1298.6 | 3036 | 15.1 | 17.0 | 26859 | 23.9 | 3784 | 3055 | 3324 | 2718.6 | 5.7 | 37.1 | 56.8 | 15.4 | 152.6 | 1.7 | 16.8 | 2028.8 | 442.1 | 52.6 | 19.6 | 27.3 | 16.0 | 9.15 | 393.9 | 20.5 | 36.0 | 120.0 | 44.7 | 156.1 | 34.3 | 22.3 | 92.3 | 61.7 | 35.4 | 6.8 | 375.7 | 3039.8 | 106.4 | 724.8 | 36.9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 101 | 1454 | 22491 | 16.1 | 25.6 | 16.5 | 31.0 | 9.3 | 20.1 | 6.82 | 26.6 | 132.3 | 6.25 | 1.89 | 5.7 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 532 | 90 | 707 | 82 | 705 | 88 | 276 | 99 | 444 | 43.6 | 31.3 | 17.9 | 15.0 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 43.2 | 7.8 | 19.7 | 2.4 | 109.0 | 27.1 | 5.13 | 38.0 | 65.3 | 17.8 | 26.6 | 5.8 | 87.4 | 11.1 | 2.0 | 34.3 | 92.3 | 100.0 | 38078.1 | 4.0 | 56.1 | 29.2 | 95.9 | 37.0 | 48.1 | 14.8 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 1.54 | 24.51 | 17.43 | 22.51 | 42.43 | 43.38 | 150.27 | 326.38 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 1.23 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 8.62 | 2.30 | 0.92 | 30.39 | 0.46 | 73.21 | 60.77 | 6.91 | 3.22 | 1.38 | 42.82 | 9.21 | 0 | 15.65 | 1.84 | 34.53 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 16.11 | 45.12 | 49.26 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 6.45 | 3.68 | 25.78 | 120.17 | 86.10 | 46.96 | 0 | 4.60 | 48.80 | 10.59 | 5.52 | 77.35 | 0.46 | 0.92 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 840.25 | 1825 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 6487 |

| 31.48 | 9.98 | 54.08 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 79487 | 9.2 | 75.6 | 25.8 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 48.9 | 17.9 | 63.7 | 8.9 | 38.3 | 100.6 | 12.5 | 9.7 | 81.8 | 18.1 | 43.1 | 56.2 | 19.5 | 50.5 | 21.2 | 46.2 | 16.9 | 27.2 | 82.1 | 78.1 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 11.3 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 24.3 | 21.8 | 10.4 | 22.6 | 12.2 | 9.4 | 2.8 | 44.2 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 21.0 | 35.3 | 1.0 | 8.9 | 14.4 | 0.71 | 78.65 | 4.3 | 66.0 | 62.3 | 39.6 | 99.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 29.8 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 15.0 | 6.9 | 0.92 | 1572 | 2464 | 1316.4 | 2842 | 17.9 | 21.6 | 42238 | 14.9 | 3433 | 2872 | 3012 | 2184.3 | 5.3 | 50.7 | 48.2 | 4.5 | 40.5 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 7671.7 | 563.9 | 55.4 | 23.8 | 32.8 | 7.5 | 8.62 | 448.4 | 23.8 | 30.4 | 126.6 | 51.9 | 158.6 | 29.3 | 13.0 | 85.5 | 40.1 | 62.2 | 7.6 | 337.3 | 1650.6 | 35.2 | 775.4 | 3.5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1108 | 1645 | 26087 | 15.6 | 21.3 | 17.5 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 16.1 | 8.62 | 25.2 | 133.9 | 7.76 | 1.99 | 6.4 | 7 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 588 | 85 | 645 | 82 | 682 | 81 | 187 | 100 | 514 | 54.5 | 38.6 | 25.9 | 14.7 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 13.9 | 2.4 | 26.6 | 2.1 | 129.8 | 31.3 | 5.06 | 39.5 | 61.9 | 17.5 | 25.0 | 4.8 | 70.6 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 29.3 | 85.5 | 100.0 | 39620.9 | 4.5 | 56.2 | 27.7 | 97.9 | 34.7 | 48.2 | 17.1 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1.52 | 11.25 | 9.52 | 26.65 | 38.50 | 50.19 | 136.11 | 108.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 2.96 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.52 | 23.90 | 2.52 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 11.32 | 0.00 | 0 | 5.03 | 1.26 | 8.81 | 1.26 | 2.52 | 1.26 | 22.65 | 5.03 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 28.94 | 50.32 | 21.39 | 18.87 | 0 | 0.00 | 28.94 | 2.52 | 1.26 | 11.32 | 2.52 | 2.52 | 2.52 | 0.00 | 265.45 | 211 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.10 | 3521 |

| 19.75 | 9.11 | 54.13 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 133210 | 6.8 | 55.4 | 19.3 | 7.6 | 13.7 | 43.0 | 17.8 | 41.3 | 6.3 | 30.5 | 52.5 | 9.3 | 16.6 | 94.1 | 5.8 | 54.3 | 55.8 | 19.7 | 45.2 | 23.3 | 50.1 | 16.1 | 30.0 | 81.1 | 130.9 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 11.2 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 22.6 | 23.8 | 11.9 | 24.6 | 12.7 | 9.9 | 2.8 | 45.8 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 20.5 | 39.2 | 4.6 | 8.0 | 13.3 | 0.77 | 79.28 | 3.7 | 72.2 | 23.1 | 38.6 | 99.3 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 19.7 | 17.5 | 11.2 | 27.8 | 3.6 | 8.6 | 12.7 | 6.8 | 0.96 | 1793 | 2317 | 1260.8 | 2914 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 36985 | 13.7 | 3343 | 2924 | 3248 | 844.5 | 0.5 | 11.1 | 58.6 | 3.8 | 402.7 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 1607.3 | 518.4 | 46.1 | 25.3 | 21.7 | 0.0 | 5.26 | 411.9 | 23.6 | 28.8 | 125.9 | 43.7 | 130.8 | 20.6 | 2.9 | 85.1 | 7.9 | 54.4 | 8.3 | 366.3 | 1831.6 | 53.4 | 824.7 | 7.9 | 2 | 74 | 2 | 0 | 93 | 122 | 11103 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 19.9 | 20.2 | 6.9 | 24.2 | 5.35 | 19.1 | 94.6 | 7.64 | 1.91 | 6.1 | 14 | 71 | 19 | 65 | 14 | 1864 | 51 | 248 | 41 | 1823 | 50 | 576 | 87 | 583 | 70.8 | 73.5 | -15.8 | 16.7 | 4.0 | 3.1 | -0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 84.3 | 11.7 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 91.7 | 16.0 | 1.77 | 31.4 | 70.1 | 11.8 | 18.9 | 2.5 | 47.2 | 8.6 | 1.9 | 20.6 | 85.1 | 63.0 | 31456.6 | 2.8 | 55.8 | 26.3 | 71.8 | 32.9 | 47.4 | 19.7 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 41.70 | 6.89 | 90.28 | 297.00 | 262.48 | 698.35 | 930.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 6.01 | 0.75 | 18.77 | 28.53 | 1.50 | 0.75 | 1.50 | 25.52 | 4.50 | 0 | 6.01 | 0.00 | 60.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.01 | 9.01 | 19.52 | 0.75 | 7.51 | 0.75 | 1.50 | 20.27 | 78.82 | 37.53 | 27.78 | 0 | 0.00 | 52.55 | 6.01 | 4.50 | 38.29 | 0.00 | 6.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 481.20 | 641 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 4041 |

| 54.83 | 10.60 | 53.59 | 108 | Schleswig-Holstein | 197264 | 5.5 | 44.9 | 22.6 | 6.4 | 11.4 | 32.3 | 22.3 | 44.5 | 6.3 | 35.9 | 114.1 | 22.7 | 19.5 | 90.7 | 9.2 | 47.5 | 58.2 | 20.0 | 51.2 | 19.8 | 45.4 | 17.1 | 32.5 | 82.1 | 136.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 11.8 | 6.8 | 4.9 | 24.9 | 23.8 | 10.2 | 22.3 | 12.0 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 44.6 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 22.2 | 35.0 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 12.1 | 0.87 | 80.58 | 3.9 | 76.8 | 10.3 | 36.3 | 100.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 22.5 | 4.0 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 10.6 | 1.11 | 1903 | 2404 | 1257.6 | 2832 | 10.1 | 11.7 | 54979 | 20.9 | 3404 | 287 | 3031 | 1344.4 | 0.9 | 11.5 | 59.8 | 26.0 | 1673.3 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 2476.9 | 490.2 | 47.9 | 23.3 | 19.9 | 12.7 | 3.14 | 406.7 | 25.6 | 28.4 | 111.1 | 56.2 | 126.2 | 31.7 | 19.2 | 83.1 | 38.5 | 40.9 | 7.5 | 474.9 | 1251.8 | 52.9 | 791.1 | 1.6 | 2 | 36 | 3 | 0 | 155 | 193 | 35799 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 27.4 | 13.0 | 7.8 | 14.9 | 4.62 | 13.5 | 71.8 | 7.77 | 2.02 | 6.9 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 31 | 13 | 1545 | 63 | 2042 | 49 | 1804 | 48 | 343 | 94 | 572 | 71.7 | 79.7 | -52.4 | 15.6 | 4.1 | 2.9 | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 23.6 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 94.4 | 15.0 | 1.85 | 21.7 | 61.0 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 2.6 | 41.8 | 9.6 | 1.7 | 31.7 | 83.1 | 71.7 | 21795.1 | 2.6 | 58.2 | 27.4 | 92.6 | 27.3 | 47.7 | 25.1 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.78 | 58.77 | 5.10 | 90.62 | 153.91 | 193.65 | 502.04 | 990.34 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 9.12 | 0.00 | 24.33 | 64.38 | 1.52 | 0.51 | 1.52 | 8.11 | 2.53 | 0 | 4.06 | 0.51 | 18.76 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 8.62 | 19.77 | 14.70 | 6.08 | 7.60 | 0.51 | 1.01 | 20.78 | 70.97 | 32.95 | 31.94 | 0 | 2.03 | 39.03 | 8.11 | 3.04 | 27.37 | 0.51 | 3.55 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 439.51 | 867 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 4296 |

The first column (AdjRate) contains age-adjusted incidence rates. The X and Y columns represent longitude and latitude. NUTS2_Fact represents government regions (Regierungsbezirke), BL_ID is the federal state (Bundesland), and EWZ is the population. The remaining columns cover socioeconomic, infrastructural, and built environment features. We will filter out only the most relevant features later.

BART requires a data.frame of predictors and a separate vector for the response variable:

psych::skew(data$AdjRate)

## [1] 3.64179

# Response variable

y <- log(data$AdjRate)

# Data.frame of predictors

data_bm <- select(data, -c(AdjRate))

Because AdjRate is highly skewed (skewness = 3.64), we apply a log transformation. Though BART is non-parametric and can handle skewed data, transforming the response variable aids in visually interpreting results.

Below is a summary of the log-transformed AdjRate:

| Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.13 | 0.7 | 1.75 | 6.51 |

First BART model

We can use default hyperparameter values for BART, but bartMachine offers a convenient tuning function called bartMachineCV to find optimal values. Because that process can be time-consuming, I’ve omitted it here. Below, I simply build a BART model using those pre-determined optimal hyperparameters.

bm_All <- bartMachine(X = data_bm, y = y,

k=2, nu=3, q=0.9, num_trees=100,

num_iterations_after_burn_in=2000,

num_burn_in = 300,

seed = 1234, verbose = FALSE)

## Warning in build_bart_machine(X = X, y = y, Xy = Xy, num_trees = num_trees, : Setting the seed when using parallelization does not result in deterministic output.

## If you need deterministic output, you must run "set_bart_machine_num_cores(1)" and then build the BART model with the set seed.

summary(bm_All)

## bartMachine v1.3.4.1 for regression

##

## training data size: n = 401 and p = 366

## built in 6.4 secs on 20 cores, 100 trees, 300 burn-in and 2000 post. samples

##

## sigsq est for y beforehand: 0.024

## avg sigsq estimate after burn-in: 0.09236

##

## in-sample statistics:

## L1 = 58.88

## L2 = 14.93

## rmse = 0.19

## Pseudo-Rsq = 0.9228

## p-val for shapiro-wilk test of normality of residuals: 2e-05

## p-val for zero-mean noise: 0.92439

The Pseudo-R² of 0.92 and RMSE of 0.19 look promising. Let’s check the error assumptions next:

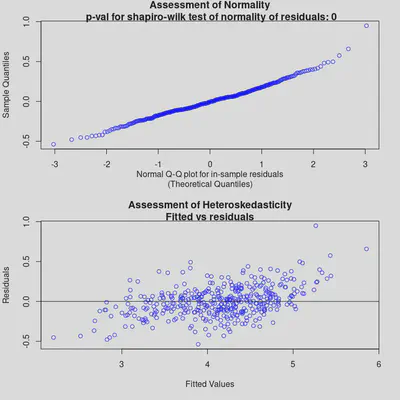

check_bart_error_assumptions(bm_All)

Both diagnostic plots look reasonable. In the second one (Assessment of Heteroskedasticity), there is a mild pattern, but not a stark one. Overall, the model seems to fit well, though it might struggle slightly with extreme values.

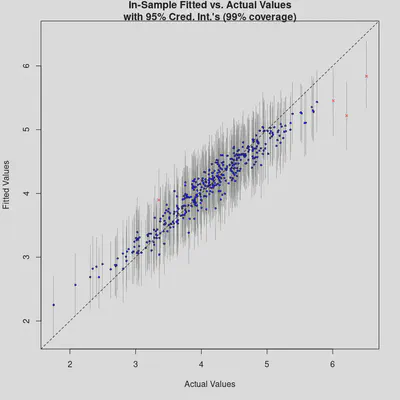

plot_y_vs_yhat(bm_All, credible_intervals = TRUE)

The “Fitted vs. Actual Values” plot also demonstrates good model performance. Again, we see that the model tends to over-predict extremely low values and under-predict extremely high values. We could also map the residuals to check for spatial clustering, but let’s first reduce the model’s complexity by removing non-important predictors.

Variable Selection

Although BART yields excellent R² values, part of its power lies in its ability to handle high-dimensional data. In large datasets, often only a fraction of the predictors significantly influence the response variable. Occam’s razor suggests favoring simpler models over overly complex ones.

The function var_selection_by_permute (introduced by (Bleich et al. 2014)) helps reduce model complexity. Feel free to skip the following code and just trust my results—this step can be time-consuming:

# Leave the num_trees_for_permute small, to force variables to compete for entry into the model!

var_sel <- bartMachine::var_selection_by_permute_cv(bm_All, num_trees_for_permute = 20)

# Look at the most important variables

var_sel$important_vars_cv

## [1] "BL_ID_Baden-Württemberg" "BL_ID_Bayern"

## [3] "BL_ID_Hessen" "ff_pop"

## [5] "hair_pp" "thea_pp"

## [7] "NUTS2_Fact_11" "NUTS2_Fact_27"

## [9] "NUTS2_Fact_40" "NUTS2_Fact_71"

## [11] "S_170" "play_dn"

## [13] "bir_km2" "cc_pop"

## [15] "sch_den" "kid_den"

## [17] "Rch_den" "S_109_2"

## [19] "EWZ" "Pop_Den"

## [21] "S_004" "S_006"

## [23] "S_020" "S_051"

## [25] "S_054" "S_066"

## [27] "S_070" "S_080"

## [29] "S_104" "S_107"

## [31] "S_115" "S_123"

## [33] "S_130" "S_146"

## [35] "S_153" "X"

## [37] "Y"

Below is the subset of important variables (grouped thematically). I also removed NUTS2_Fact and BL_ID:

data_subset <- data_bm %>%

select(c(

# Geographical Units

X, #Longitude

Y, #Latitude

# Political units

S_109, #Rural/Urban

# Socioeconomic

EWZ, #Population

Pop_Den, #Population density

S_004, #Unemployment rate under 25

S_006, #Household income per capita

S_020, #Employment rate 15-<30

S_051, #Voter participation

S_054, #Apprenticeship positions

S_066, #Household income

S_070, #Deptors rate

S_080, #Recreationl Space

S_104, #Income tax

S_107, #Steuerkraft

S_115, #Regional population potential

S_123, #Child poverty

S_130, #IC train station access

S_146, #Commuters >150km

S_153, #Foreign guests in tourist establishments

S_170, #Longterm unemployment rate

# Built environment

Rch_den, #Church density

play_dn, #Playground density

bir_km2, #Biergarten per km²

ff_pop, #Fast food places per capita

hair_pp, #Hairdresser per capita

thea_pp, #Theatre per capita

cc_pop, #Community centre density

sch_den, #School density

kid_den #Kindergarten density

))

Second BART model

With this subset of key predictors, I now build a new BART model (again using pre-determined optimal hyperparameters):

bm_final <- bartMachine(X = data_subset, y = y,

k=3, nu=3, q=0.99, num_trees=225,

seed = 1234, verbose = FALSE)

## Warning in build_bart_machine(X = X, y = y, Xy = Xy, num_trees = num_trees, : Setting the seed when using parallelization does not result in deterministic output.

## If you need deterministic output, you must run "set_bart_machine_num_cores(1)" and then build the BART model with the set seed.

summary(bm_final)

## bartMachine v1.3.4.1 for regression

##

## training data size: n = 401 and p = 31

## built in 6.5 secs on 20 cores, 225 trees, 250 burn-in and 1000 post. samples

##

## sigsq est for y beforehand: 0.185

## avg sigsq estimate after burn-in: 0.12859

##

## in-sample statistics:

## L1 = 90.04

## L2 = 34.13

## rmse = 0.29

## Pseudo-Rsq = 0.8236

## p-val for shapiro-wilk test of normality of residuals: 0.00156

## p-val for zero-mean noise: 0.95958

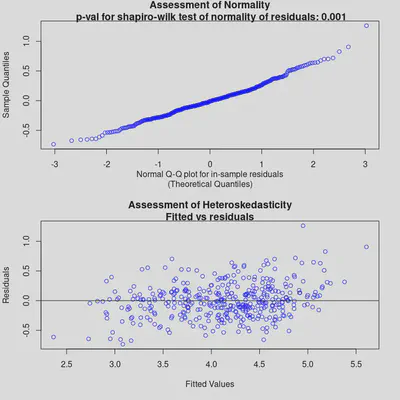

Compared to the first model, the Pseudo-R² decreases from 0.92 to 0.82, equating to a 11% reduction in explained variance. The RMSE increased from 0.19 to 0.29, indicating that the final model predicts the age-adjusted incidence rate of COVID-19 with an accuracy of roughly +/− 1.3 cases per 100,000. Let’s again check the diagnostic plots:

check_bart_error_assumptions(bm_final)

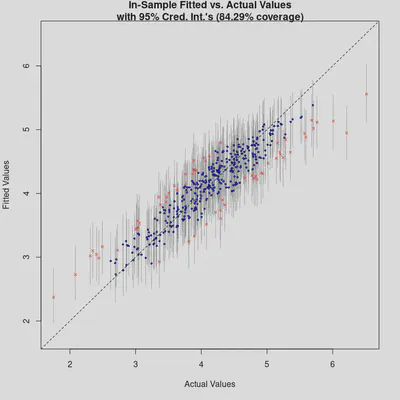

plot_y_vs_yhat(bm_final, credible_intervals = TRUE)

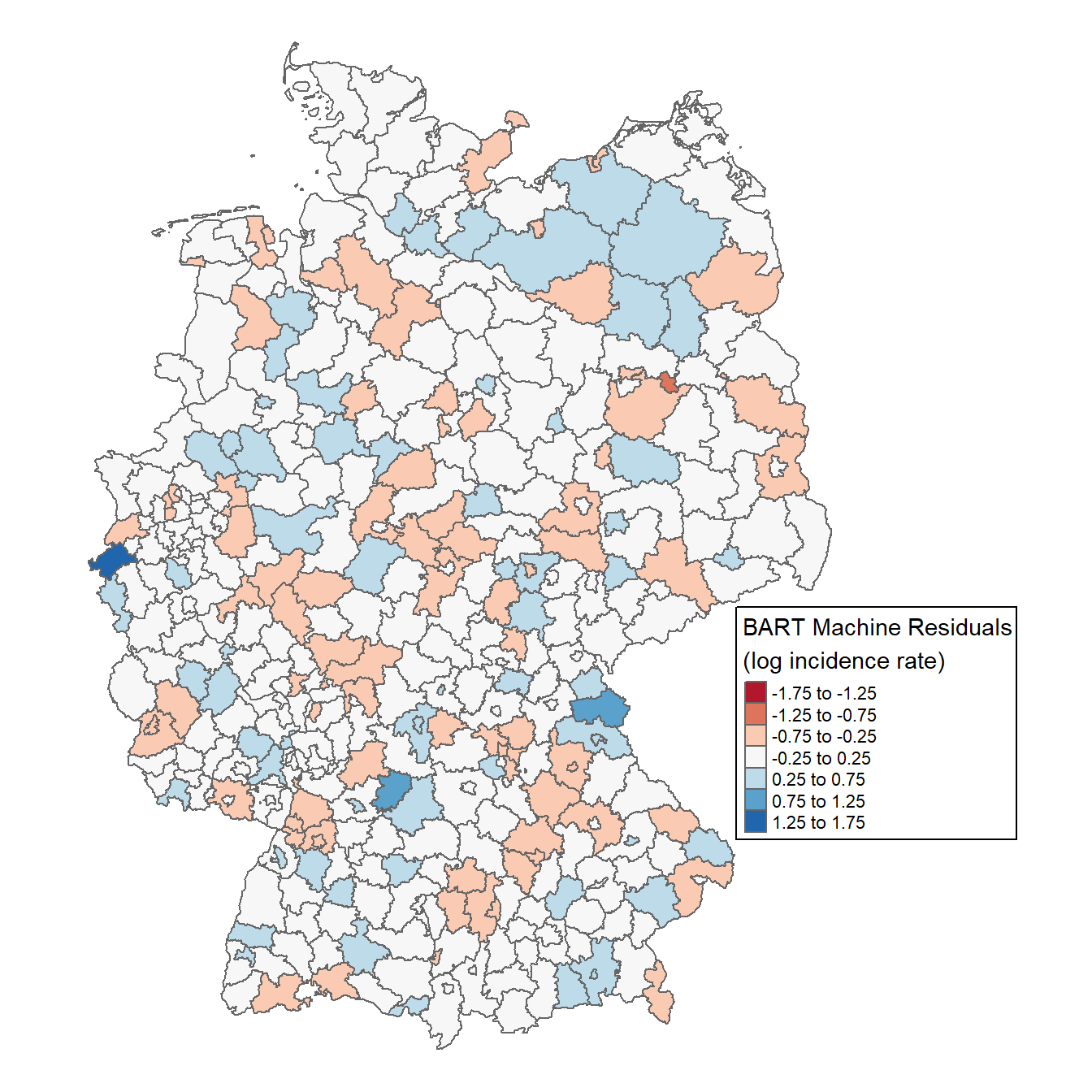

The “Fitted vs. Actual Values” plot shows okay performance, though more points lie outside the confidence intervals. Next, let’s map the residuals to check for any spatial clustering.

Spatial autocorrelation

We can quickly visualize residuals by linking them to a shapefile of German counties (NUTS3). Any obvious clustering of positive or negative residuals would indicate spatial autocorrelation.

library(sf)

library(RColorBrewer)

library(tmap)

# Download shapefile

shp <- read_sf("https://github.com/STBrinkmann/data/raw/main/RKI_sf.gpkg")

# Sort shapefile, that it has the same order as the data_subset

shp <- shp[order(match(shp$EWZ, data_subset$EWZ)),]

# Join residuals to shapefile, then map residuals

shp$resid <- bm_final$residuals

tm_shape(shp) +

tm_polygons(col="resid",

title="BART Machine Residuals\n(log incidence rate)",

breaks=seq(-1.75, 1.75, 0.5), midpoint=NA, palette="RdBu") +

tm_layout(frame = FALSE,

inner.margins=c(0.02, 0.02, 0.02, 0.20),

legend.position = c(0.7, 0.22),

legend.frame = TRUE,

legend.outside = FALSE,

bg.color = "white")

No clear geographical pattern emerges, suggesting no strong spatial clusters. For a formal test, we can compute Moran’s I. I will not explain Moran’s I in this post, but I would highly recommend these posts: Intro to GIS and Spatial Analysis and Spatial autocorrelation analysis in R.

library(spdep)

# Define neighboring polygons

nb <- poly2nb(shp, queen=TRUE)

# Assign weights to each neighboring polygon

lw <- nb2listw(nb, style="B", zero.policy=TRUE)

# Compute Moran's I statistic using a Monte-Carlo simulation

MC <- moran.mc(shp$resid, lw, nsim=99)

MC

##

## Monte-Carlo simulation of Moran I

##

## data: shp$resid

## weights: lw

## number of simulations + 1: 100

##

## statistic = 0.061242, observed rank = 97, p-value = 0.03

## alternative hypothesis: greater

Moran’s I ranges from -1 to 1, where values closer to ±1 indicate strong positive/negative spatial autocorrelation, and 0 implies randomness. With a Moran’s I of 0.06 (p=0.03), we conclude there is no significant spatial autocorrelation in the residuals.

Partial Dependence Plots

So far, we’ve built and refined a BART model to predict age-adjusted incidence rates of COVID-19 in German counties. However, our main goal is to explore the data rather than simply predict. BART’s high R² suggests it captures these non-linear relationships, and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) let us visualize and interpret them (Friedman 2002; Scarpone et al. 2017, 2020).

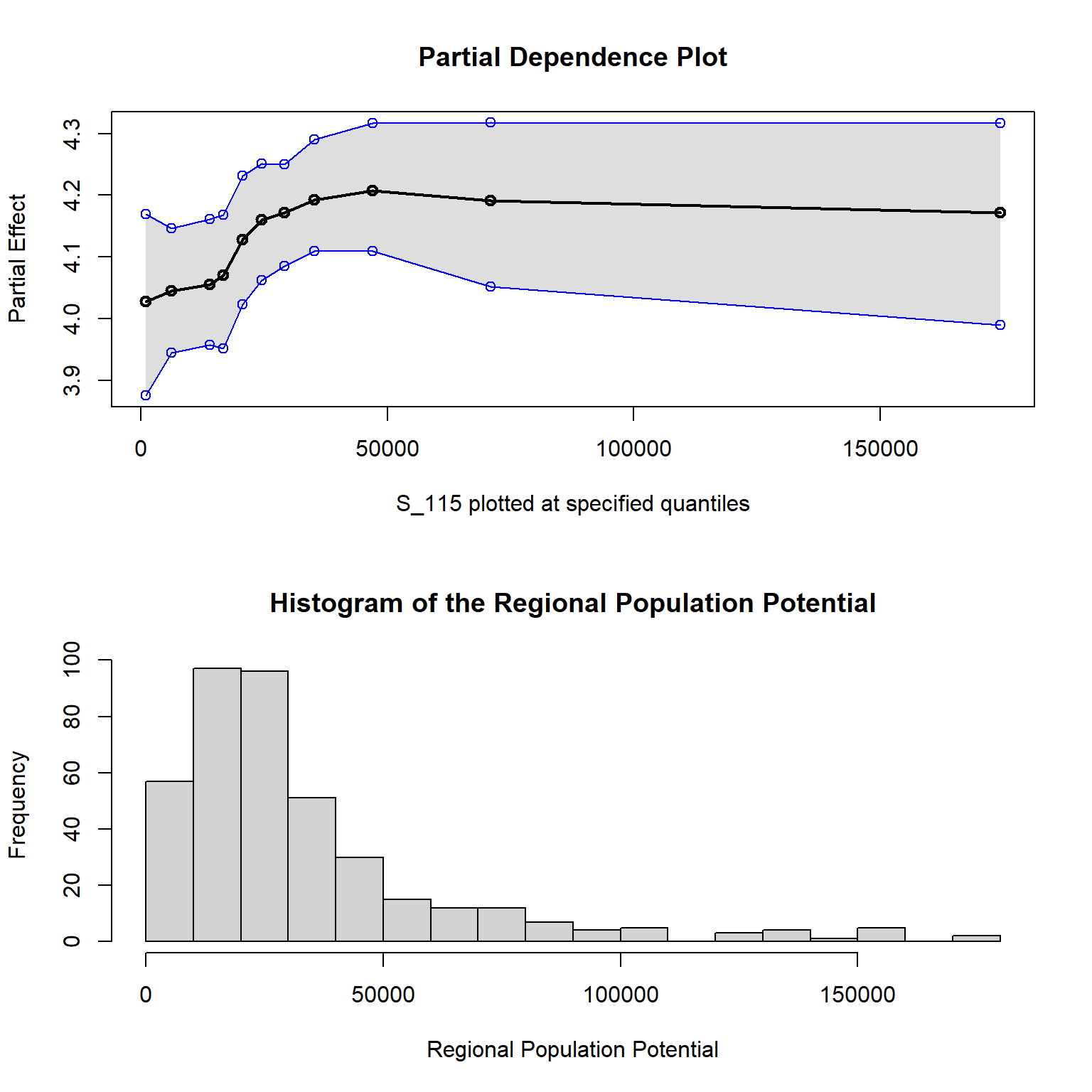

Although the pdp is great for computing PDPs, it does not directly support bartMachine. Fortunately, bartMachine provides its own PDP function, pd_plot. Below is a demonstration using S_115 (Regional Population Potential):

# Set parameters to plot PDP top and histogram bottom

par(mfrow = c(2,1))

pd_plot(bm_final, "S_115", levs = c(0.0, seq(0, 1, 0.1), 1))

## ...........

hist(bm_final$X$S_115, 20,

main = "Histogram of the Regional Population Potential",

xlab = "Regional Population Potential")

Regional population potential measures the likelihood of direct human interactions in a region. This PDP suggests minimal marginal change in incidence at the lower end of the distribution, implying less chance of viral contagion in areas with fewer human interactions. The curve rises notably between the 20th and 80th percentiles (14,016 to 47,067), indicating a strong non-linear effect on incidence rates.

To log-transform the x-axis for clarity, you would need a custom PDP function, since pd_plot does not support that directly. I wrote a variant that returns ggplot2 objects GitHub), which lets you customize plots extensively.

Below is a multi-panel PDP from our publication, showing the top 10 variables. You can see more details and interpretation of these variables here.

Conclusion

In this post, we developed and refined a BART-based workflow for modeling age-adjusted COVID-19 incidence rates across German counties. We started by applying BART to a high-dimensional dataset of socioeconomic, infrastructural, and built environment predictors, then used a permutation-based variable selection technique to isolate the most important features. Although BART can handle dozens or even hundreds of predictors, our results showed that only a smaller subset of variables drove most of the explanatory power.

By visualizing these relationships with Partial Dependence Plots, we uncovered non-linear effects and interactions that more conventional methods might have missed. These plots also help “open the black box,” translating an otherwise opaque machine learning model into actionable insights. Although BART performed well overall, we observed that it tended to under-predict very high values and over-predict very low ones, highlighting the challenges of modeling extreme outcomes.

In future posts, I will focus on out-of-sample validation to confirm the model’s robustness and detect any lingering overfitting issues. I also plan to dive deeper into how the variable selection procedure can be tuned for different research contexts. Ultimately, BART’s Bayesian foundation—combined with flexible tree-ensemble strategies—offers a compelling toolkit for complex, spatially heterogeneous data like COVID-19 incidence.

References

Bleich, Justin, Adam Kapelner, Edward I. George, and Shane T. Jensen. 2014. “Variable Selection for BART: An Application to Gene Regulation.” The Annals of Applied Statistics 8 (3). https://doi.org/10.1214/14-aoas755.

Breiman, Leo. 2001. “Statistical Modeling: The Two Cultures (with Comments and a Rejoinder by the Author).” Statistical Science 16 (3). https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1009213726.

Chipman, Hugh A., Edward I. George, and Robert E. McCulloch. 2010. “BART: Bayesian additive regressiontrees.” The Annals of Applied Statistics 4 (1): 266–98. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-AOAS285.

Friedman, Jerome H. 2002. “Stochastic Gradient Boosting.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 38 (4): 367–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-9473(01)00065-2.

Kapelner, Adam, and Justin Bleich. 2016. “bartMachine: Machine Learning with Bayesian Additive Regression Trees.” Journal of Statistical Software 70 (4). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v070.i04.

Scarpone, Christopher, Sebastian T. Brinkmann, Tim Große, Daniel Sonnenwald, Martin Fuchs, and Blake Byron Walker. 2020. “A Multimethod Approach for County-Scale Geospatial Analysis of Emerging Infectious Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Case Study of COVID-19 Incidence in Germany.” International Journal of Health Geographics 19 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-00225-1.

Scarpone, Christopher, Margaret G. Schmidt, Chuck E. Bulmer, and Anders Knudby. 2017. “Semi-Automated Classification of Exposed Bedrock Cover in British Columbia’s Southern Mountains Using a Random Forest Approach.” Geomorphology 285 (May): 214–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.02.013.