Visibility - Sensitivity Analysis

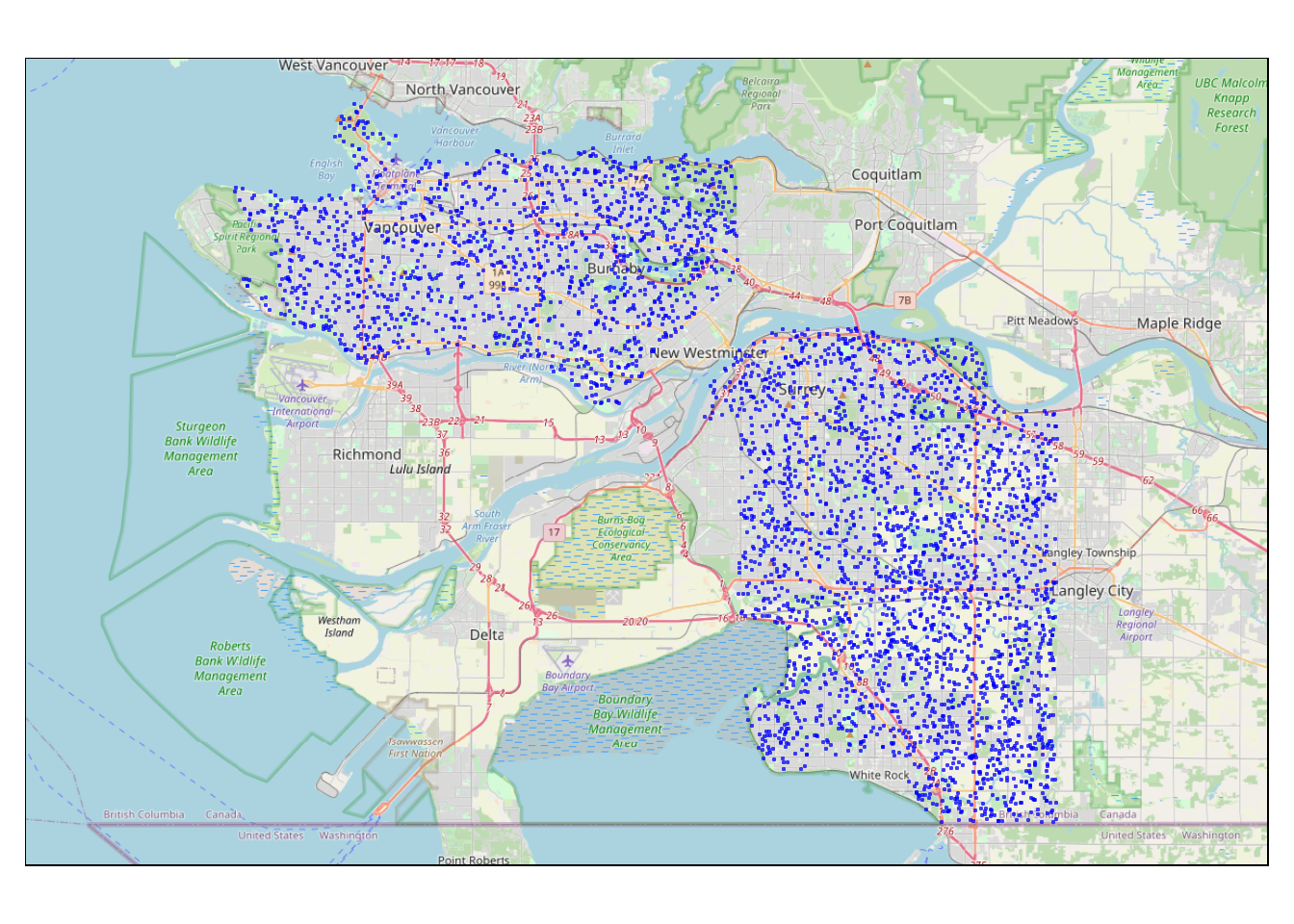

As part of my Bachelor Thesis I am analyzing the effects of visible green- and bluespaces on mental health based on a medical study in Vancouver. The area of interest covers Vancouver City, Burnaby and Surrey.

To analyze the effect of visible greenness I’ll be using the Viewshed Greenness Visibility Index (VGVI). The VGVI expresses the proportion of visible greenness to the total visible area based on a viewshed. The estimated VGVI values range between 0 and 1, where 0 = no green cells are visible, and 1 = all of the visible cells are green. In a recent post I have demonstrated how to calculate the VGVI, and in my R package GVI (currently only available on GitHub) I have provided fast functions to compute the VGVI.

To calculate the VGVI for an observer, the viewshed of this point needs to be computed first - hence the name Viewshed Greenness Visibility Index. The viewshed function of the GVI package does exactly that. The basic idea is to apply a buffer on the observer position. Now we can “simply” check every point in this area, whether it is visible or not.

To do so, we need a Digital Surface Model (DSM), Digital Terrain Model (DTM) and the observer location as input data for the viewshed function.

# Load libraries

library(dplyr)

library(sf)

library(GVI)

library(terra)

workdir <- "H:/Vancouver/Vancouver_RS_Data/"

# Load DSM and DEM

dsm <- rast(file.path(workdir, "DSM.tif"))

dtm <- rast(file.path(workdir, "DTM.tif"))

# Sample observer location

st_observer <- sfheaders::sf_point(c(487616.2, 5455970)) %>%

st_sf(crs = st_crs(26910))

# Compute Viewshed

viewshed_1 <- GVI::viewshed(observer = st_observer,

dsm_rast = dsm, dtm_rast = dtm,

max_distance = 250, resolution = 1,

observer_height = 1.7, plot = TRUE)

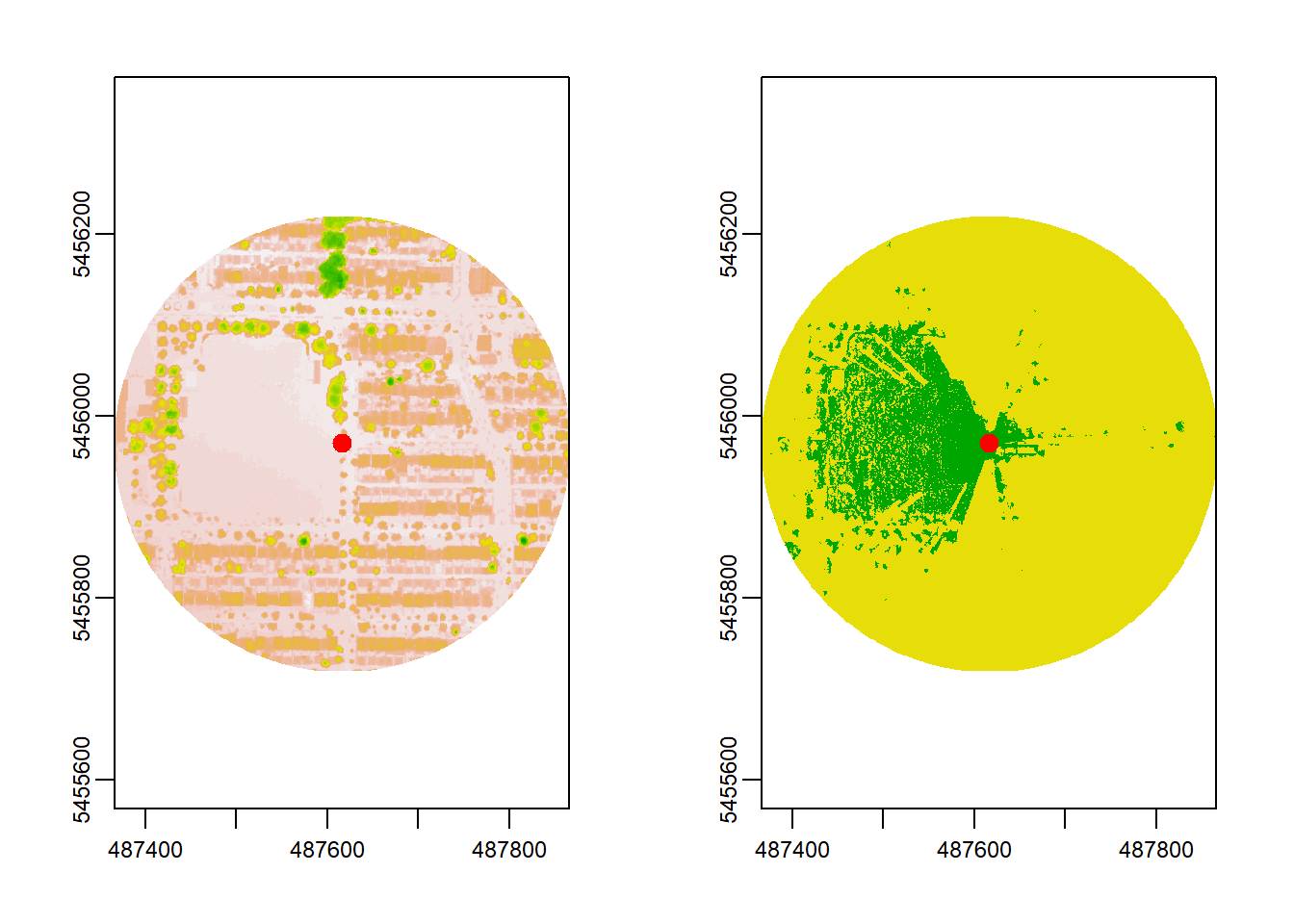

In the plot above, the Digital Surface Model (DSM) is visualized on the left. The viewshed is shown on the right, where green = visible and yellow = no-visible area. The observer in the example - visualized as the red dot - can see far over the sports field to the west and has little visibility to the east.

Next, we would compute the VGVI based on the viewshed and a greenspace mask. However, in this post I would like to focus on the two parameters distance and resolution. Distance describes the radius of the buffer around the observer location. The resolution parameter describes the resolution that the rasters should be aggregated to. High resolution yields the most realistic results, but on cost of computation time.

Sensitivity Analysis

When computing the VGVI for a single, or few points, you wouldn’t need to consider using a lower resolution or adjusting the maximum distance. The computation time is rather low even at high resolution with a high maximum distance (e.g. 800m with 1m resolution: 5.5 secs). However, when computing the VGVI for a larger area - like the whole City of Vancouver - it is very important to consider these parameters. In the following I conduct a sensitivity analysis for the two parameters.

Samples

For the sensitivity analysis of the two parameters I’ll use a representative sample of 4000 observer locations.

set.seed(1234)

# Grab 4000 random points. The Van_2m_xy.gpkg file has 108.320.000 points

fid_sample <- sample(1:108320000, 4000)

# Read the shapefile using an SQL statement

my_query = paste("SELECT * FROM \"Van_2m_xy\" WHERE fid IN (", toString(fid_sample), ")")

sf_sample <- st_read(file.path(workdir, "Van_2m_xy.gpkg"),

query = my_query,

quiet = TRUE)

Distance

In the example above I have used a distance of only 250 meters. Below I have computed the VGVI for the same observer location, but with a 800 meter radius.

# Compute Viewshed

viewshed_2 <- GVI::viewshed(observer = st_observer,

dsm_rast = dsm, dtm_rast = dtm,

max_distance = 800, resolution = 1,

observer_height = 1.7, plot = TRUE)

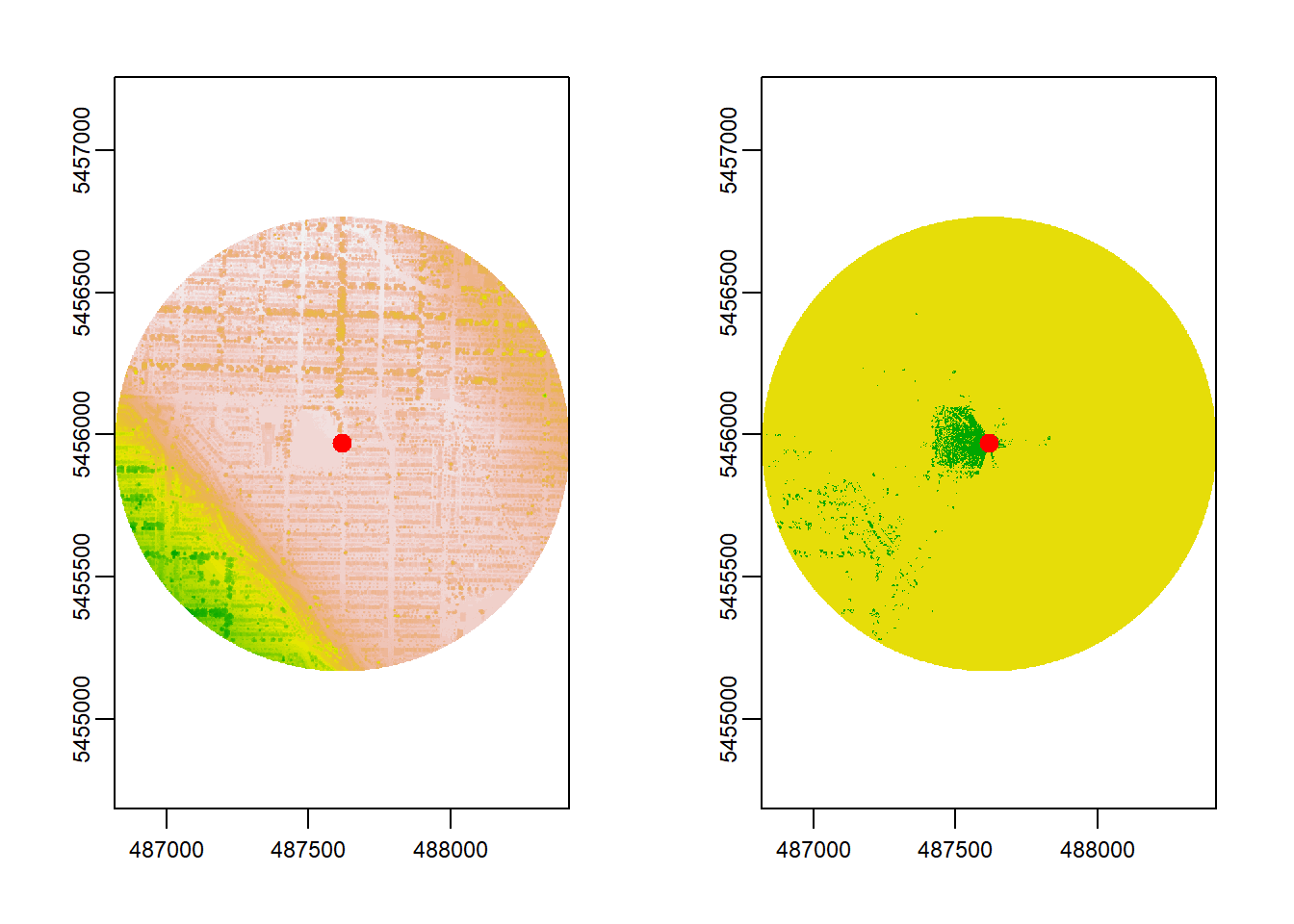

Increasing the distance to 800 meters doesn’t really affect the visible area. Most of what can be seen at this specific observer location, is withing the smaller 250 m radius. But the computation time decreases from 5.5 to 0.3 seconds!

Therefore, it’s important to investigate if the relationship between distance and visible area. The function below calculates the proportion of visible area for each distance value of the viewshed raster.

visibleDistance <- function(x) {

# Get XY coordinates of cells

xy <- terra::xyFromCell(x, which(!is.na(x[])))

# Calculate euclidean distance from observer to cells

centroid <- colMeans(terra::xyFromCell(x, which(!is.na(x[]))))

dxy = round(sqrt((centroid[1] - xy[,1])^2 + (centroid[2] - xy[,2])^2))

dxy[dxy==0] = min(dxy[dxy!=0])

# Combine distance and value

cbind(dxy, unlist(terra::extract(x, xy), use.names = FALSE)) %>%

as_tibble() %>%

rename(visible = V2) %>%

arrange(dxy) %>%

group_by(dxy) %>%

# Mean visible area for each distinct distance value

summarise(visible = mean(visible)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

return()

}Let’s apply it on the second viewshed:

| Distance | Visibility |

|---|---|

| 1 | 100.0% |

| 2 | 100.0% |

| 3 | 100.0% |

| 4 | 100.0% |

| 5 | 100.0% |

| 796 | 0.2% |

| 797 | 0.1% |

| 798 | 0.1% |

| 799 | 0.1% |

| 800 | 0.2% |

To find the specific distance threshold of my area of interest, I’ll use the sample of 4000 points and compute the viewshed and proportion of visible area for each distance value.

for(i in 1:nrow(sf_sample)) {

# Viewshed

this_dist <- viewshed(observer = sf_sample[i, ], max_distance = 1000,

dsm_rast = dsm, dtm_rast = dtm) %>%

# Costum function

visibleDistance()

# Add to "out"

if (i == 1) {

out <- this_dist

} else {

out <- rbind(out, this_dist)

}

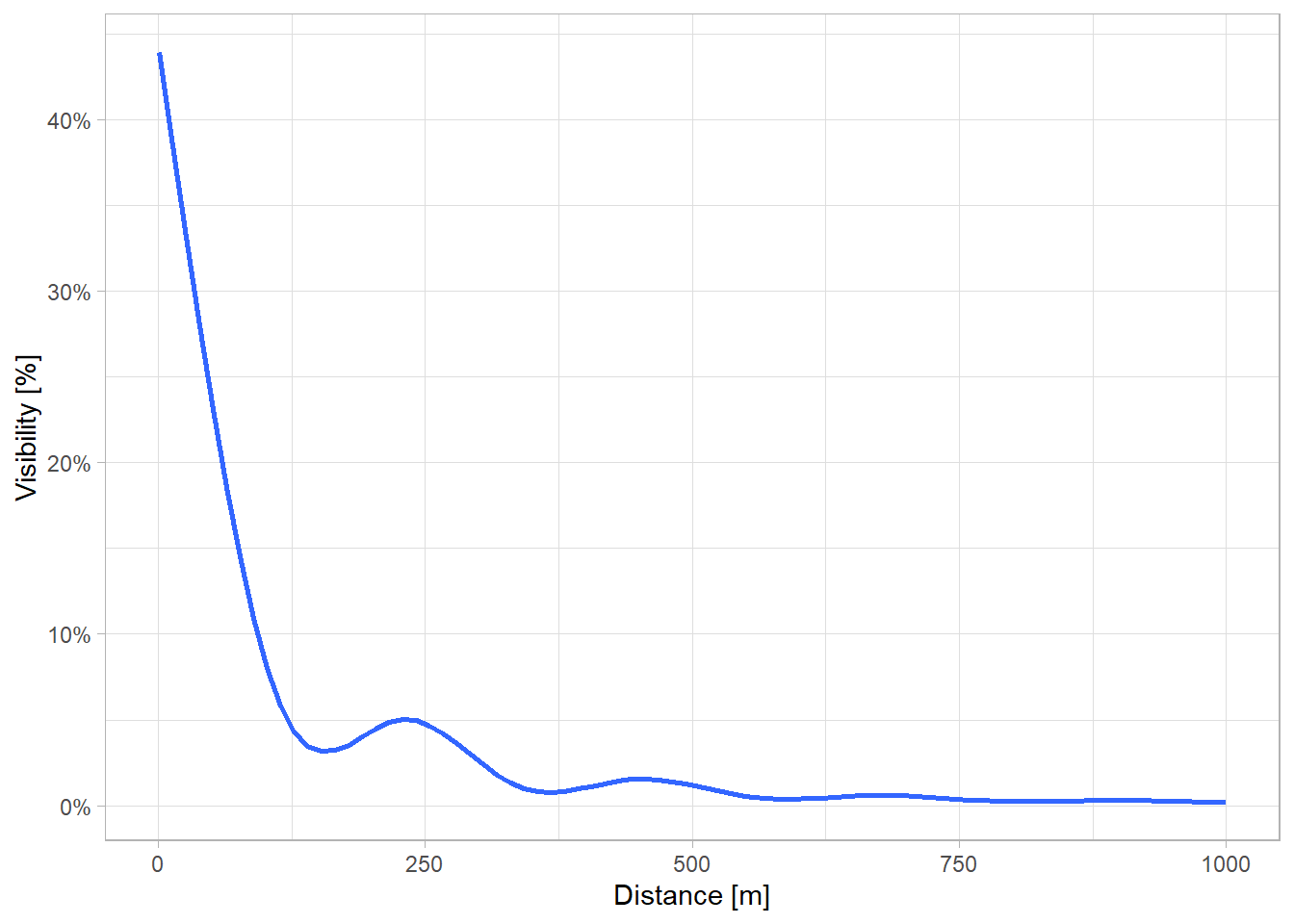

}The plot below indicates, that visibility decreases with increasing distance. Interestingly, there are two distance levels where visibility increases locally, at 250 m and 500 m. This might be due to city planning effects. Most points are located at streets, maybe parks are planned to be evenly distributed in the Vancouver Metropolitan area for close, equal access.

Based on this analysis I set the distance parameter to 550 meters.

Resolution

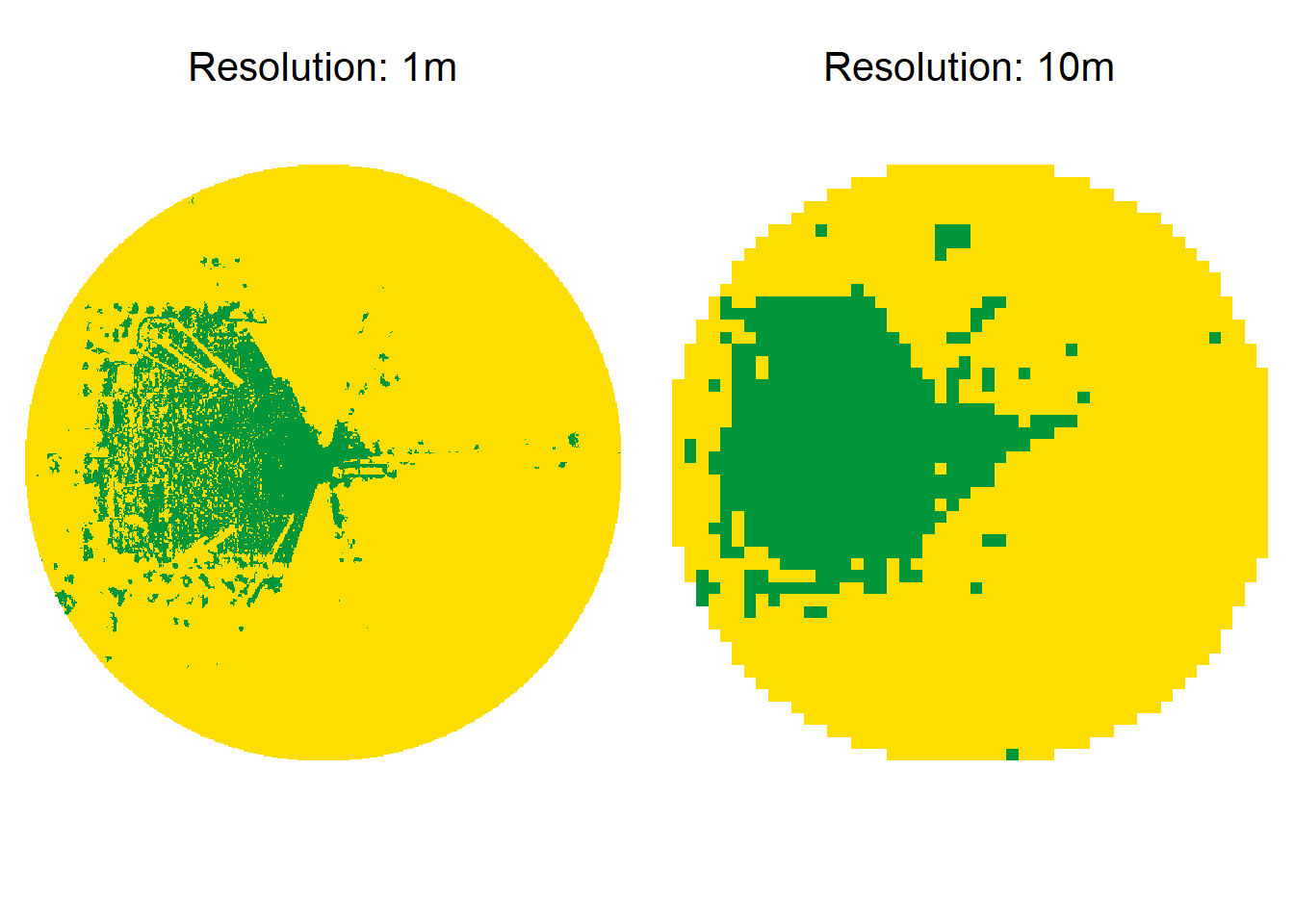

The resolution parameter describes the resolution that the rasters should be aggregated to. Using the distance value of 550 meters, the viewshed with a 1 m resolution has 1.210.000 cells and takes 1 second. A viewshed with 5 meter resolution has 48.400 cells and takes only 0.5 seconds to compute. However, higher resolution yields in more accurate results. Below I have provided an example for comparison.

The function below calculates the similarity of visibility for each resolution compared to the 1 meter resolution.

compare_resolution <- function(observer, dsm_path, dtm_path) {

viewshed_tbl <- lapply(c(1, 2, 5, 10), FUN = function(x) {

# Get values of viewshed with resolution x

time_a <- Sys.time()

all_value <- viewshed(observer = observer, dsm_rast = rast(dsm_path), dtm_rast = rast(dtm_path),

max_distance = 550, observer_height = 1.7, resolution = x) %>%

values() %>%

na.omit()

time_b <- Sys.time()

# Return Distance, proportion of visible area and computation time

return(tibble(

Resolution = x,

Similarity = length(which(all_value == 1)) / length(all_value),

Time = as.numeric(difftime(time_b, time_a, units = "secs"))

))

}) %>%

do.call(rbind, .)

viewshed_tbl %>%

rowwise() %>%

mutate(Similarity = min(viewshed_tbl[1,2], Similarity) / max(viewshed_tbl[1,2], Similarity)) %>%

return()

}The boxplots below confirm the assumption, that similarity decreases with increasing resolution. Mean computation time for 1 m, 2 m, 5 m and 10 m resolution was 4.80 seconds, 1.05 seconds, 0.85 seconds and 0.75 seconds, respectively. A resolution of 2 meters seems to be a optimal compromise, as it has a ~75% similarity, but the computation time decreases to about \(\frac{1}{5}\), too.

Conclusion

In this post I have conducted a sensitivity analysis on the parameters distance and resolution for the viewshed function in the Vancouver Metropolitan Area. The thresholds for the distance and resolution is 550 meters and 2 meters, respectively.

The complete study area contains 108.320.000 points, computation time on a high performance server is ~20 days. Therefore, it is important to critically think about these parameters beforehand.